Aftertwentyfive Collective Platform [2016]

/// A seek for common ground to build up commonality in gated settlements for the sake of all shareholders by reshaping repeating physical elements of gated settlements

Brief: Physical interventions in gated settlements adopting participation of investors, inhabitants and municipal authorities in order to obtain social, cultural, ecological benefits in micro and macro scales via a digital platform, municipal requirements and added-values generated by investors

Location: Istanbul / Turkey

Sort: Teamwork with İlke Zeyfeoğlu & Derya İyikul / Istanbul Technical University, Architectural Design Master Program (M.Sc.)

Supervisors: Prof.Dr. Ayşe Şentürer & Assoc.Prof.Dr. Nurbin Paker & Assoc.Prof.Dr. Aslıhan Şenel & Res.Asst.PhD. Özlem Berber

#istanbul #urbansprawl #gatedsettlements #commonality #commonground

#istanbul #urbansprawl #gatedsettlements #commonality #commongroundIf we look at the history of urbanization in Istanbul we can point out the year 1950 as a breaking moment. Even if before that date, the lodging examples like worker dwellings, cooperatives etc. is able to be seen, rural-urban migration has played a major role in urban transformation of Istanbul. By starting from this date “fast-transformation / urbanization” has manifested itself in three main phases; gecekondu, post-gecekondu (built-sell) and mass housing. After the second half of the year 1980, “spontaneous urbanization” has been replaced in Turkey with a new urbanisation form of what guided by the expanding real estate market with large capital investments. In this process, large plots on the periphery and prestigious lands in the city’s central areas were opened to settlement quickly with legal zoning regulations (Kurtuluş, 2005). In the late 1990s, the process of public housing accelerated and the spread of Istanbul has increased synchronously (Danış&Pérouse, 2005). This monopolisation order has caused emerging of sites with towers rising on the ground, surrounded by walls separating them from real life; briefly, gated settlements. Moreover, this process has stirred up the propagation of a new typology to the entire city.

Today West Ataşehir is mostly composed of “gated settlements” and located away from the central spot of the city. In the region, residential settlements pop up with human-scale-exceeding high walls reinforced by barbed wires, palm trees and ivies behind the walls which block the public eye out of settlements. With sheltered structure of gates including security officers inside and camera monitoring system, intention of isolation is demonstrated clearly.

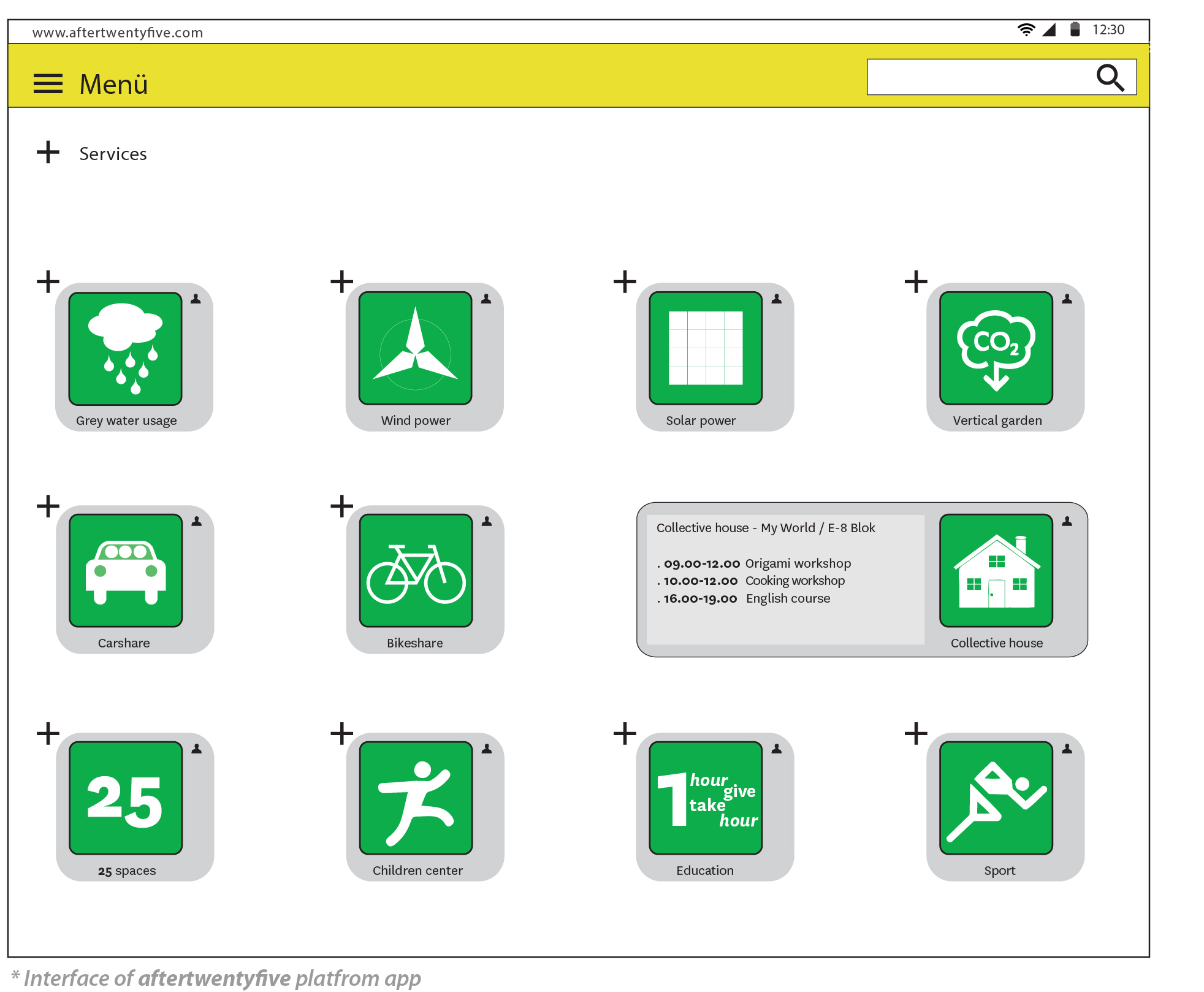

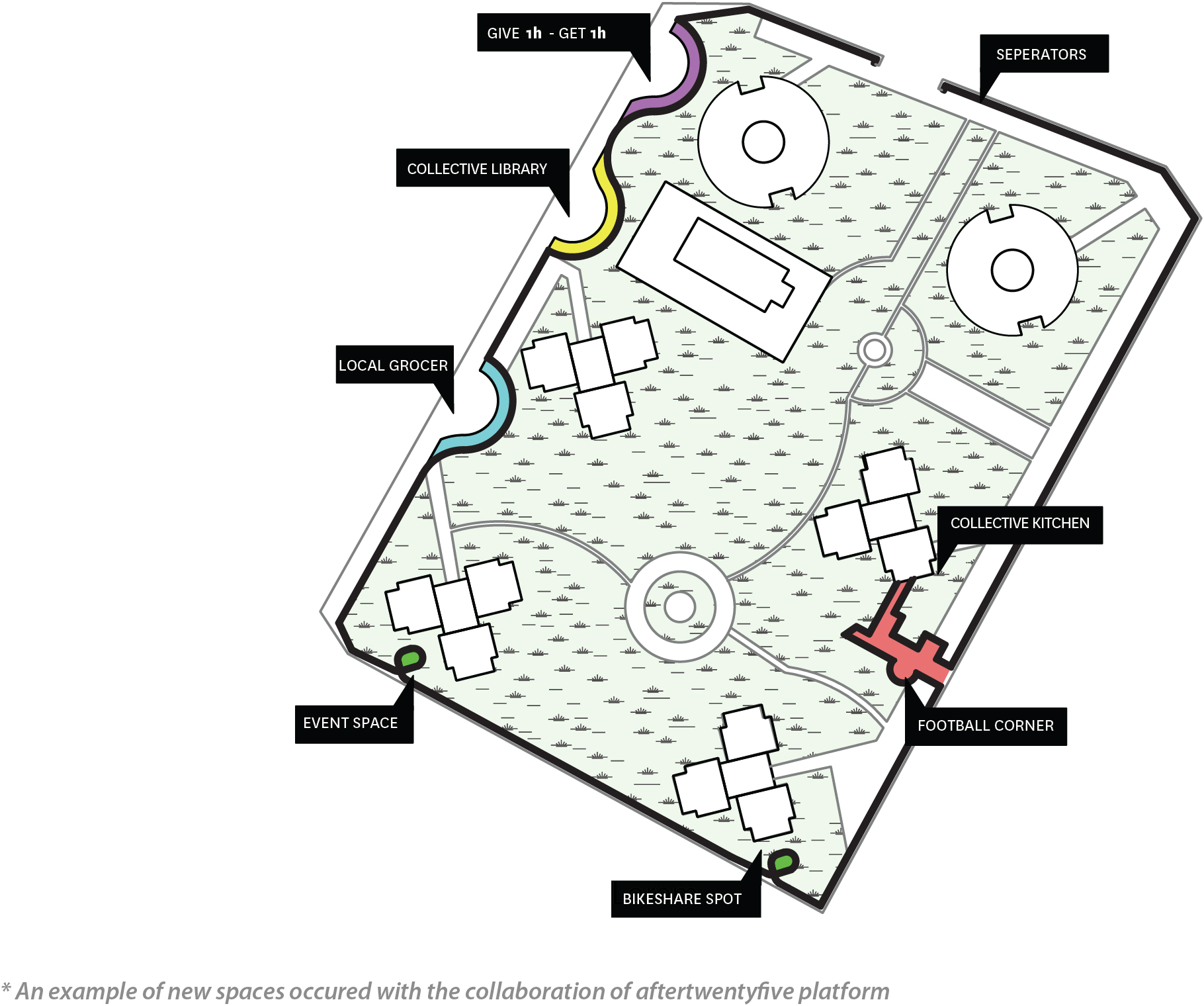

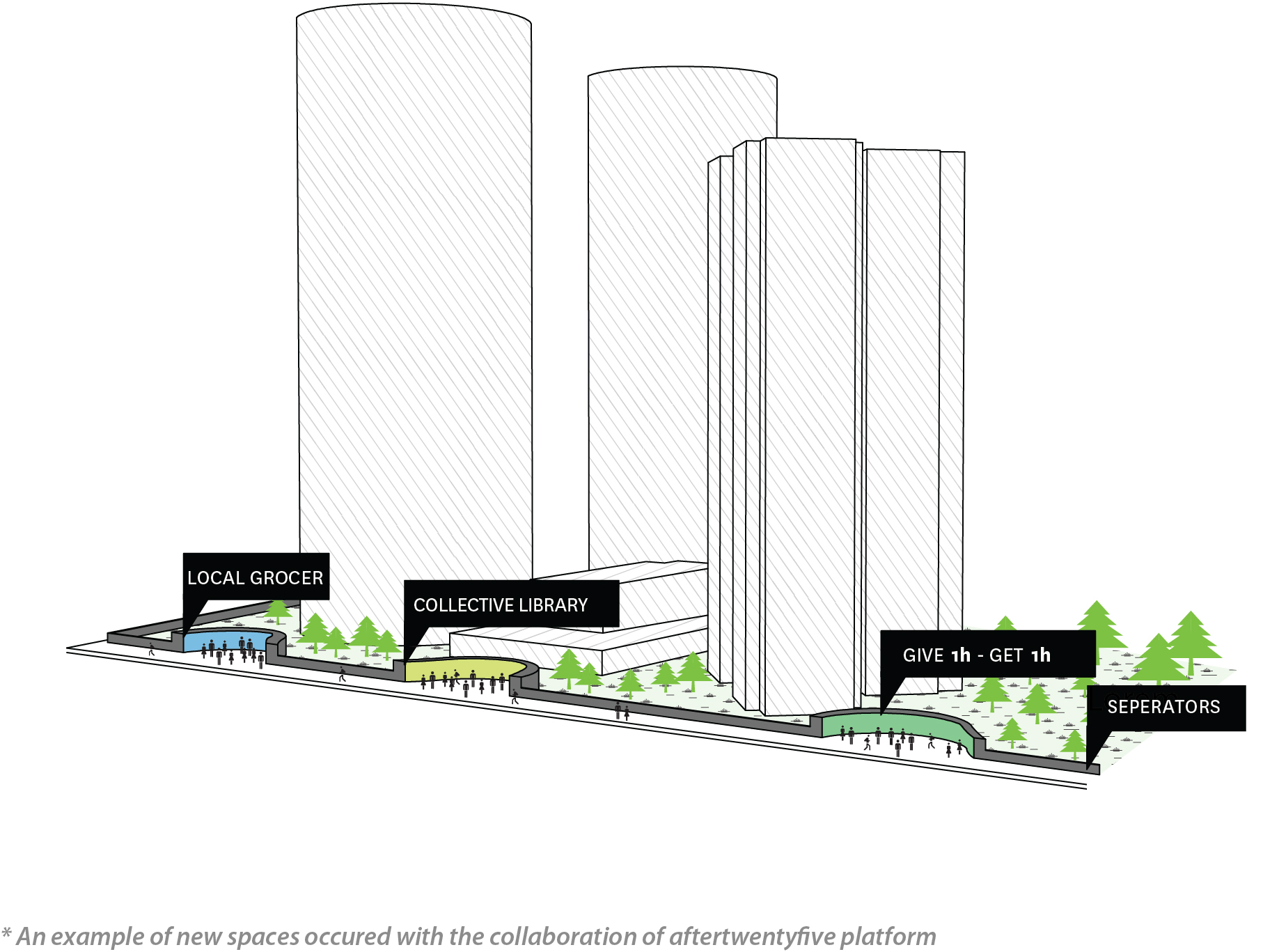

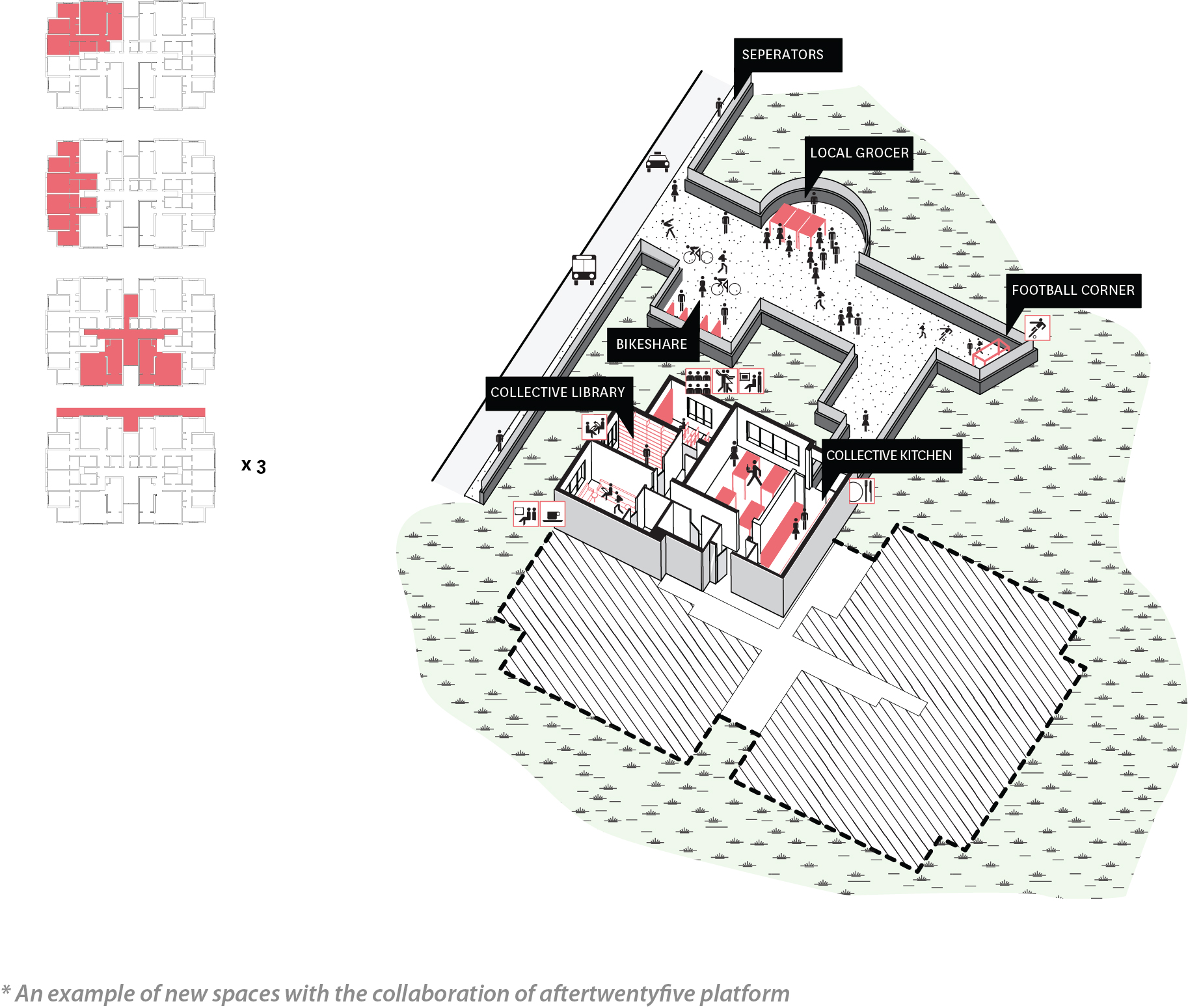

Proposal problematises isolation issue and tries to find a common ground where an optimised collective commonality is formed with its spatial expansions. To achieve this, the project brings up participatory spirit of social media, interest of investors and inhabitants and executive power of municipal authorities and melts into an alternative system. Performative architecture and design inserted into those highly isolated islands aims people to gather around natural resources, social communication, local economy. Definition of common areas is reconfigured and redefined via benefit of shareholders which are municipalities, investors as well as citizens and a collective management is eventually proposed as a common ground. The proposal does not aim to destruct the existing system but it aims to create a niche where all shareholders extract benefits from it. In that sense the project tries to bring up an “inclusion” to the existing method of space generation. Aimed commonality is generated first via “after twenty-five” digital platform providing organisation for use of the reserved areas created by various special manipulations. Moreover, the platform supports creation of plus value initiatives and tries to be “guide” for prospective gated communities. Although designed platform itself might be seen as coming together, it provides a virtual space organised by users and transformation of the virtual energy to real one which takes place in those spaces created within the scope of project.

Home has become a commodity in time with technology and modernisation and almost an object of desire. With this transformation of house notion, the dream of “a better life” has come to the state as exhibited in various media in a seductive manner which has nothing to do with its first function of sheltering. Moreover, several complex meanings like prestige, status, safe havens in the chaos of metropolis are assigned to the notion of house (Artun & Ojalvo, 2012). Gated communities are designed with those motivations and constitute “defined neighbourhoods” thanks to their marketing visualisations. In those defined neighbourhoods, spaces to be shared are reserved and monitored for only residents of settlements. Streets, parks, gathering spaces, gardens do not showcase the same publicity as equivalent examples which can be found in conventional neighbourhoods (Blakely & Snyder, 1997). Theoretically every residents have their own “public space” and there is no need to seek out for places to socialise out of settlements. This excluding language of building act is adopted repeatedly and the results are spread around the city with its copy-paste solutions by privatising the land as well as taking from the public without giving some benefits back in return. Moreover, this manner is courageously promoted in the real estate market. Moreover, isolated neighbourhoods with high security walls and barbed wires do not establish any connections with each others in the urban scale too as they all have the same negative attitude to maintain the fixed typology. As result of physically disconnected island structures, ghettos are created in absence of built environment which allow users individual stimulation and social communication. The collapse of the public sphere in case of continuation of this state of alienation emerges as inevitable (Kurtuluş, 2005, Danış & Pérouse, 2005).

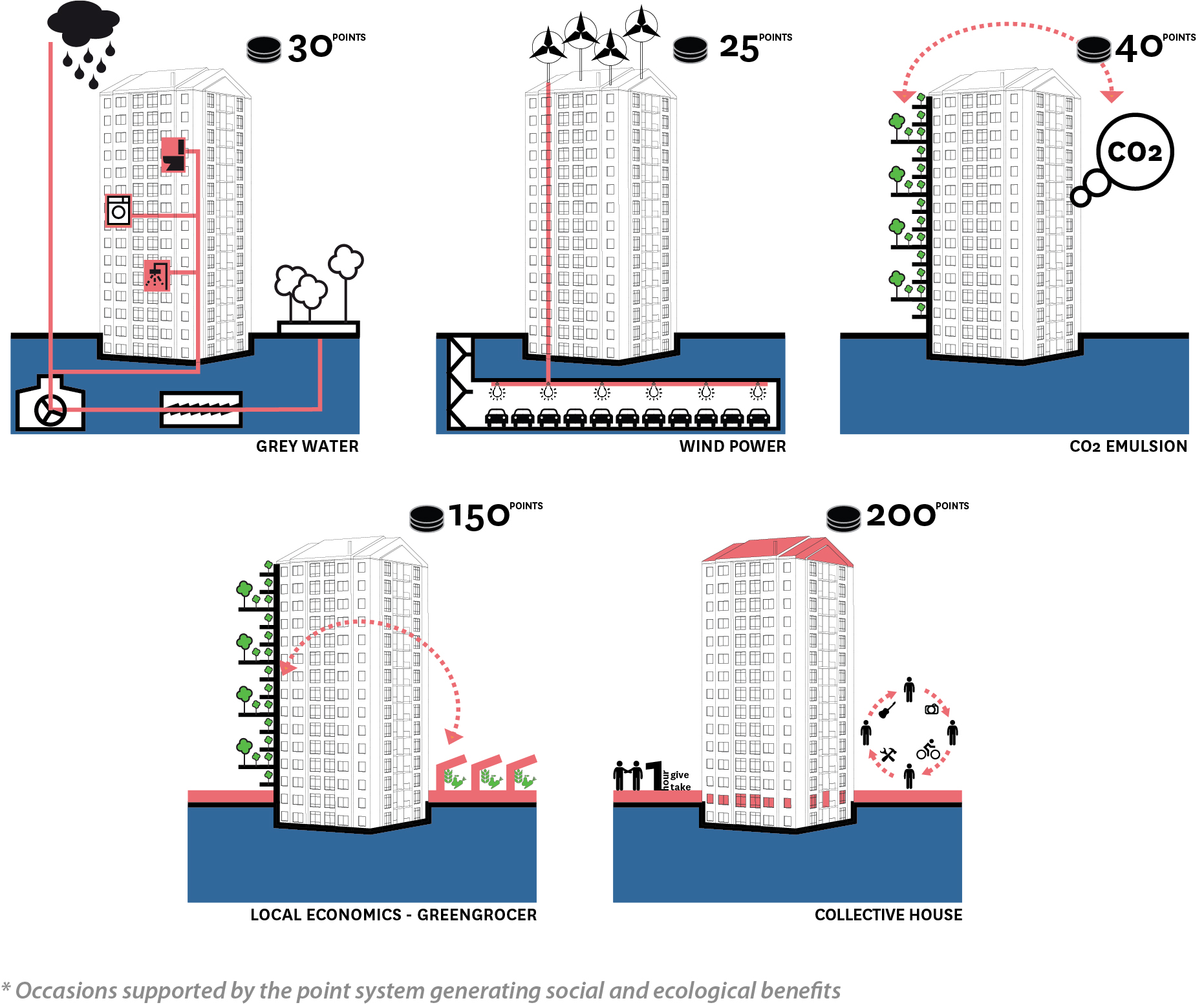

West Ataşehir with a great number of gated settlements repeating in residential area is chosen as field of study to develop an alternative proposal within the scope of the project which is an urgent call for commonality in the notion of housing arranged via some regulations implemented. The proposal aims to strengthen weak social, spacial and urban relations caused by current settlement layouts, to optimise needs, to encourage a commonality by manipulating the existing physical structure of gated settlements such as walls, facades, places reserved in buildings and the landscape. To play the game by rules and to secure its maintenance, the proposal defines so-called 25% rule which is a municipal requirement for construction license in planing. The requirement asks contractors to reserve 25% from any built environment to generate spaces which constitute infrastructure for social, cultural and economical exchange among users. In return they gain an added value for their investments thanks to point system of aftertwentyfive digital platform.

Aftertwentyfive is an online platform which seeks to create new spaces with the contribution of inhabitants who are defined as the new activist group of era (Offe, 1999). This group of people are highly educated, skilled labour and mostly university students. Moreover they tend to organise themselves easily in a horizontal hierarchy in digital platforms as reaction to current political, social problems. In the light of these facts, the platform aims to create a new commonality which is also supported by municipal regulations.

To maintain and optimise the new order, interest of investors plays also a crucial role as much as inhabitants and has to be considered. Ideally, investors have to generate an added-output to generate an added-value so that that they can transform it into new investments to make more added-value (Harvey, 2008). What matters is the added-value generated itself. It has to be embraced by all shareholders to function in the long term. In this sense, point system created via the online platform is a triggering and motivating tool for the added-value aforementioned as it grades not only users but also housing blocks and eventually the whole settlement based on interventions adopted. The more spacial intervention creating social, ecological, economical benefits is provided the more points are earned via the online platform which increase investment value in the eyes of investors.

The initial aim is to transform social skills of digital platform users who are the main inhabitants in the region into physical encountering spaces thanks to proposed digital platform. With the help of point system, it is aimed to make investors part of this transformation as they obtain added-values in return. In time, promising results from micro scaled enhancement to macro scaled enhancements via encouragement of sustainable usage of natural sources could be also extracted.

Blakely, E. & Snyder, M.G. (1997) “Fortress America; Gated Communities in the United States”, Brookings Institution Press, Washington D.C.

Danış, A.D. & Pérouse J.F. (2005) “Zenginliğin Mekanda Yeni Yansımaları: İstanbul’da Güvenlikli Siteler”, Toplum ve Bilim Dergisi, n.104, s.92-123

Harvey, D. (Eylül-Ekim 2008) “The Right to the City”, New Left Review, n.53, s.23-40.

Kurtuluş, H. (2005) “Kente Bir Sosyo-Mekansal Ölçek Olarak Bakmak ve Kentsel Dönüşüm”, Evrensel Kültür Dergisi, n.164, s.60-64

Offe, C. (1999) “Yeni Sosyal Hareketler: Kurumsal Politikanın Sınırlarının Zorlanması”, Yeni Sosyal Hareketler, Kenan Çayır (ed.), Kaknüs Yayınları, İstanbul